For millennia, Homer has been widely considered the first author in history. However, archaeological discoveries reveal that a woman in ancient Mesopotamia signed her work over 4,000 years ago, predating the famed Greek poet by fifteen centuries. This groundbreaking finding redefines our understanding of the origins of authorship and highlights the often-overlooked contributions of women to early literature.

The figure at the center of this historical reassessment is Enheduanna, a high priestess of the moon god Nanna in the Sumerian city-state of Ur, dating back to around 2300 BCE. Her existence challenges long-held assumptions about the development of written expression and the roles women played in ancient civilizations. The rediscovery of her work is prompting a reevaluation of historical narratives and the recognition of previously marginalized voices.

Who Was Enheduanna?

Enheduanna lived in what is now southern Iraq, and held a significant position as both the daughter of King Sargon of Akkad, founder of the first Mesopotamian empire, and the high priestess of Nanna. Her title, “Enheduanna,” translates to “high priestess, ornament of the sky,” though her personal name remains unknown. She wasn’t simply a religious figure; she wielded considerable political and religious power.

Crucially, Enheduanna is recognized as the earliest known author to sign her work. Her writings blend poetry, spirituality, and political strategy, offering a unique insight into the cultural and religious landscape of the time. This act of authorship, claiming intellectual ownership of her texts, is what distinguishes her as a pivotal figure in literary history.

An alabaster disc discovered in Ur depicts Enheduanna, high priestess of the moon god Nanna. The relief shows a ritual scene with a priest making a libation before a four-tiered altar (left), accompanied by three figures, including Enheduanna in a praying posture (third figure from the right). Mefman00, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons, Penn Museum, Philadelphia, United States

An alabaster disc discovered in Ur depicts Enheduanna, high priestess of the moon god Nanna. The relief shows a ritual scene with a priest making a libation before a four-tiered altar (left), accompanied by three figures, including Enheduanna in a praying posture (third figure from the right). Mefman00, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons, Penn Museum, Philadelphia, United States

Writing, Power, and Spirituality

The development of cuneiform writing originated in Mesopotamia around the mid-fourth millennium BCE, initially as an administrative tool for economic record-keeping and taxation. By Enheduanna’s time, however, it was evolving beyond purely practical applications to encompass religious, philosophical, and aesthetic expression. Writing became a sacred art, associated with the goddess Nisaba, patron of scribes, grains, and knowledge.

Enheduanna’s work exemplifies this shift. Her writings combine deep religious devotion with explicit political messaging, serving to legitimize Akkadian dominance over Sumerian city-states through a shared language, faith, and unified theological discourse. This demonstrates the power of early literature to shape and reinforce political structures.

A Major Body of Work

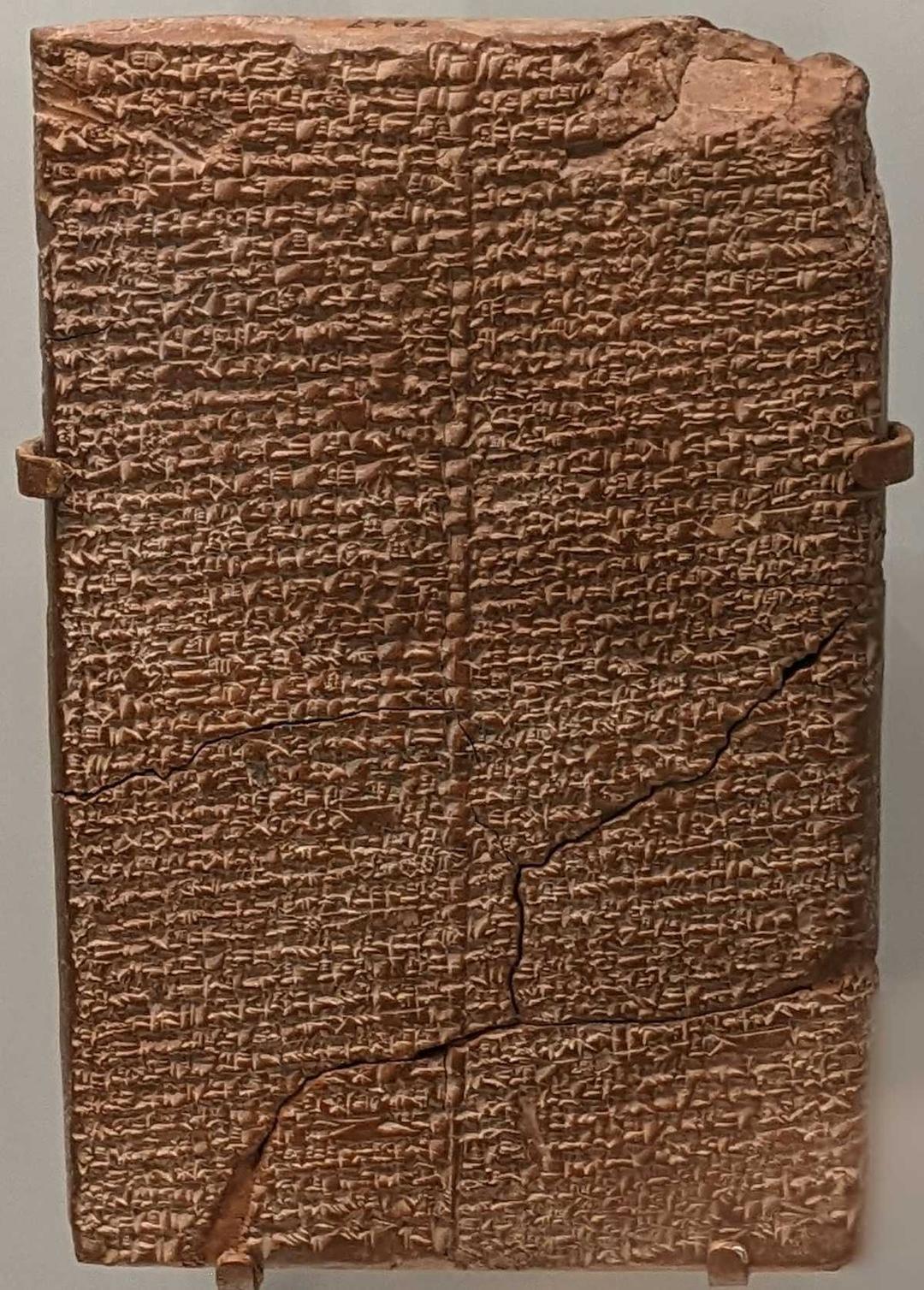

Several compositions attributed to Enheduanna have survived, most notably The Exaltation of Inanna, a lengthy hymn celebrating the goddess of love and war, Inanna. In this work, she pleads for the goddess’s assistance during a period of exile. This text is often considered her most personal and powerful piece.

Also preserved are the Temple Hymns, a collection of forty-two hymns dedicated to various temples and deities of Sumer. Through these hymns, Enheduanna created a spiritual map of the territory, emphasizing the close connection between religion and political power.

Additional fragmented hymns, including one dedicated to her god Nanna, further contribute to her significant literary legacy.

These texts are not merely religious in nature; they are sophisticated in construction, rich in symbolism, emotion, and political vision. Enheduanna emerges as an intermediary between the gods and humanity, and between her father, the emperor, and the conquered cities.

Why Has She Been Overlooked?

It’s surprising that Enheduanna is absent from most school curricula and university literature courses. Outside of specialists in ancient history or gender studies, her name remains largely unknown.

Tablet, copy of the hymn Inanna B/Ninmesharra – The Exaltation of Inanna, attributed to Enheduanna. © Masha Stoyanova, Wikimedia Commons, CC0, Penn Museum, Philadelphia, United States

Tablet, copy of the hymn Inanna B/Ninmesharra – The Exaltation of Inanna, attributed to Enheduanna. © Masha Stoyanova, Wikimedia Commons, CC0, Penn Museum, Philadelphia, United States

Some scholars suggest that Enheduanna’s obscurity stems from a systemic erasure of women from cultural history. As art historian Ana Valtierra Lacalle points out, for centuries, the presence of female scribes or artists in antiquity was denied, despite archaeological evidence confirming their literacy and administrative capabilities.

Enheduanna was not an isolated case; her existence demonstrates that women actively participated in the development of Mesopotamian civilization, both in the religious and intellectual spheres. The fact that she is the first known person to sign a literary text in their own name warrants a prominent place in human history.

The first person known to have signed a text in their own name deserves a prominent place in the history of humanity

She represents not only a foundational moment in literary history but also embodies the capacity of women to create, think, and exercise authority from the dawn of written culture. Her voice, etched onto clay tablets, resonates across millennia, offering a unique perspective and a compelling argument for a more inclusive understanding of our shared past.