There are days when the tech world feels perfectly stable. Brands have clear rivals, logos feel like flags, and one can, with a degree of naiveté, easily define where each boundary lies. For years, Apple was synonymous with PowerPC. Intel was the alternative. And Steve Jobs repeated this so often it felt like a geographical, rather than technological, truth.

I remember 2005 as one of those pivotal years: a mix of excitement and apprehension. Apple had recently experienced a resurgence. The iMac had turned things around, and the iPod had put music in everyone’s pockets. But there was still a fragility in the air, as if it all could crumble with a single misstep. Then came the rumors. Intel. Intel inside a Mac. It felt like a betrayal, a surrender, the end of an era.

For months, online forums, user groups, and tech cafes buzzed with speculation. If Apple switched to Intel, the magic would be lost. The difference would disappear. The Mac as we knew it would be over. No one could fully articulate why, but everyone felt it: it smelled like the end of the world.

When the competitor moved in

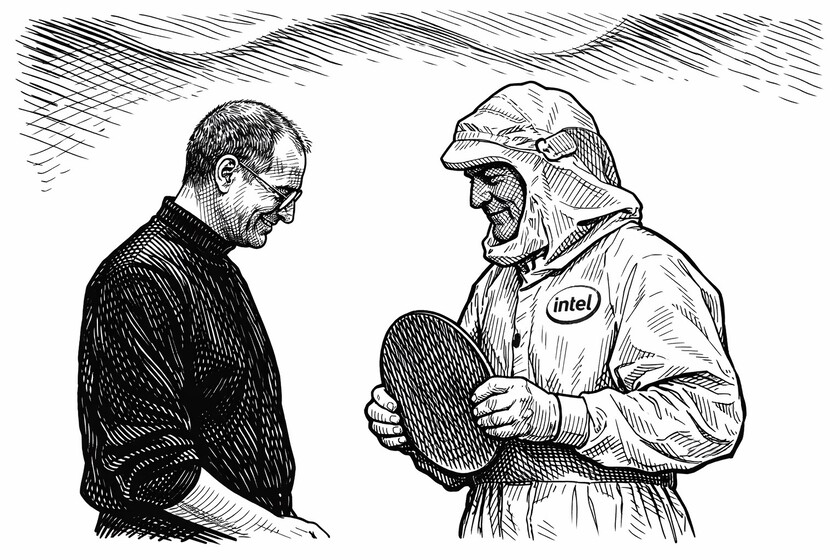

Steve Jobs had long positioned Intel as the other. The efficient, industrial, and cold competitor. We were different. Creative. Powerful. And we were, rightfully so. The PowerPC offered genuine processing power, a point Apple emphasized in its marketing. This move represented a significant shift in Apple’s strategy, signaling a willingness to prioritize performance and efficiency over brand loyalty.

But the world was beginning to shift towards mobility and efficiency. Jobs spoke of something that sounded technical and abstract at the time: watts per performance. How much energy is required to achieve a certain level of performance. It wasn’t a conversation suited for a flashy presentation, but it was the right one. The PowerPC was struggling to keep pace.

Apple abandoned PowerPC in favor of Intel, citing efficiency and improved watts per performance, a decision that shocked many loyalists. Jobs then revealed that the Mac used in the demonstration already featured an Intel processor, signaling the future had arrived.

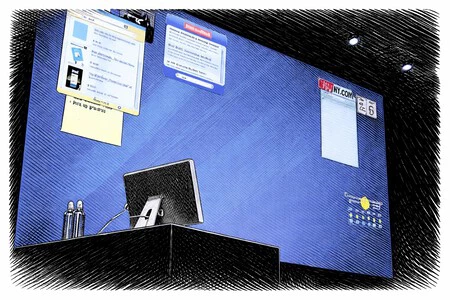

I remember the day of the keynote with a mix of disbelief and fascination. Jobs displayed “It’s true” on the screen, with the ‘E’ in Apple slightly askew, mirroring the Intel logo. It was an elegant joke, a wink, a recognition – and simultaneously, a confession. Apple was going to employ Intel processors.

There were tense smiles. Awkward silences. Purists felt like something intimate was being taken from them. At the GUM Alicante, the Macintosh user group I attended from Elche, faces were long. This wasn’t just a technical change. It felt like someone had touched the company’s DNA, and for many of us, our identity.

Then came the masterstroke. Jobs pointed to the Mac he had been using throughout the presentation. That Mac, he said, already had an Intel processor inside. We had been looking at the future without realizing it.

The day hell froze over

The truly unsettling part came next. Windows on a Mac. Installing the enemy natively. That truly felt like hell freezing over. For years, Windows had been the boundary. What we were not. What we didn’t want to be. And suddenly it became another option, official and endorsed from the stage. What was Jobs saying?…

I remember conversations filled with drama. “If I can install Windows on a Mac, what’s the difference?” The question made sense in 2005. Apple was still not the undeniable giant it is today. It had just survived a near-terminal decade. The feeling of fragility lingered.

Over time, I understood something I hadn’t seen then. Allowing Windows didn’t weaken the Mac. It strengthened it. It alleviated the fears of many. People who hesitated because they felt they were abandoning something familiar found a safety net. If this doesn’t convince me, I can always go back. And in that margin of reassurance, everyone stayed, and I know many of you are still here today. Not out of obligation. By choice.

Allowing Windows on the Mac, rather than weakening it, strengthened it and attracted fresh users. Apple demonstrated a commitment to a vision, not a specific technology.

It wasn’t the end of the world. It was the beginning of another. Apple didn’t dissolve into Intel. It became stronger. It sold more Macs. It attracted users who would never have dared to cross the bridge without that implicit promise of compatibility.

That move also offered a deeper lesson. Apple wasn’t married to a specific technology. It was married to a vision. If the vision required a change of partner, it changed. If the competitor offered a longer roadmap, it shook hands.

And perhaps most importantly: Apple had already stared into the abyss. It had almost disappeared in the nineties. When you’ve looked into the void and come back, fear transforms. Since that day, I firmly believe that the end of the world for Apple was more difficult than many thought. Apple had learned to mutate.

The end of the world that never comes

Years later, when Apple Silicon arrived and the company once again designed its own chips, I understood that the seed was planted in 2005. In that uncomfortable decision, in that apparent concession. Switching to Intel wasn’t a defeat. It was a strategic learning experience about control, efficiency, and the importance of mastering architecture.

What seemed like a concession was actually a springboard. Apple learned what it was like to depend on someone else’s roadmap. It learned what it meant to negotiate timelines, power consumption, and limitations. And years later, it decided it didn’t want to be there again. Apple Silicon didn’t come from nowhere.

The world didn’t end when Intel moved in. The world changed. And Apple, once again, decided to change with it. Sometimes we believe the apocalypse is disguised as a catastrophe. Other times, it arrives as a slide with a slightly misaligned ‘E’.

And we understood – fortunately, it’s never too late – that some endings don’t bring ash: they bring seeds.

In Applesfera | Pellizcar una pantalla